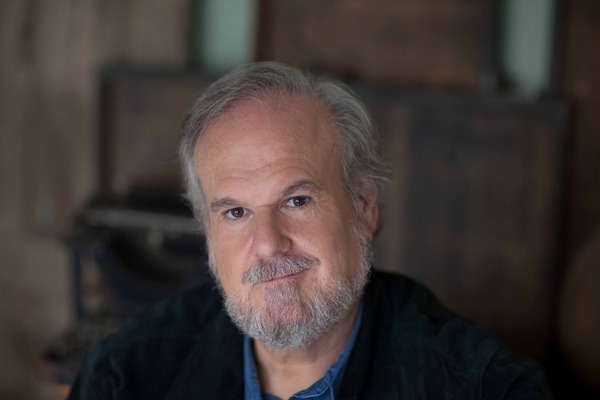

By Kathy Sands-Boehmer

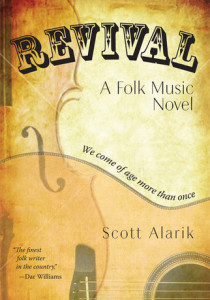

Pete Seeger has called Scott Alarik “one of the best writers in America.” It’s true. Alarik is one of the most foremost purveyors of prose about folk music who has even put words on paper or a computer screen. Known primarily as a folk music critic and analyst, who covered folk music for the The Boston Globe for more than 20 years and was a regular contributor to public radio, he tried his hand at writing a novel and the result was Revival: A Folk Music Novel. This book highlights the highs and lows of a seasoned musician and a brand-new-to-the-scene musician and their musical connection on and off the stage. It’s a story about the folk community, the under the radar society of people who search for the music that speaks to them — those who mine for musicians in church coffeehouses, festivals, and open mics. This is their world. This is my world.

Your novel, Revival, strikes a chord with music lovers of all kinds, but especially those who know and love what is referred to as the “subterranean” world of modern folk music. As someone who has written about this scene so much over the years, are you surprised that not more people have discovered the great quality of the music and the warmth and intense power of the folk community?

That’s one reason I wrote Revival. One of the great things about fiction is that it allows us explore unfamiliar worlds in fun, human ways. I wanted to show the folk world as it exists today, to make it welcoming and accessible to new people, and to let folk fans appreciate it in new ways. It’s such a human music today, happening all over the country at vibrant community venues. At one point, a character in the book reflects that “tradition is just another word for community.”

One of the great things about fiction is that you can show, not tell, as the late Bill Morrissey used to say. I wanted to reveal the folk world through characters the reader gets to know and care about. There’s such a craving today for art that’s about us, about how our lives actually feel to us. That’s still the job of folk music, just as it was in the old days. As a character says in Revival, folk’s mission, then and now, is “to make our most ordinary mornings the stuff of song.”

Revival is a love story but it’s so much more than that. I’m not a musician — merely a music fan who promotes shows and artists — but I view your book as a primer to musicians, both experienced and brand new to this world. Have you received this kind of reaction from those who have read the book?

At a folk festival, a young songwriter named Brie told me she’d given up music. Revival, she said, “reminded me why we write songs, and that it’s not about the business.” Now she’s writing songs again. I can’t imagine a better compliment. I’ve heard from many musicians who’ve told me Revival helped them understand their careers better, not only the business stuff, but the creative processes of writing songs, collaborating, working on arrangements, recording, and performing.

But I also wanted to write a novel for people who are not performers. I think the struggles of the characters can be meaningful to anybody. The main characters, Nathan Warren and Kit Palmer, are musicians at very different places in their lives. Kit’s just starting her career, and Nathan thinks he’s failed at everything. His life turned out so differently than his dreams for it, and I think that’s a struggle most middle-aged people go through.

I also think people can relate to Kit’s struggles to balance her strengths with her shortcomings, and how she wants her strong ambitions to be about more than vanity and self-interest. She wants to create a life of purpose and meaning. That’s a tension most of us wrestle with when we’re young.

Beyond that, I wanted Revival to be about the wonder of music, to explore its mystery and emotional power. What is it about music that travels so deeply inside us? Both the main characters love music in ways that transcend their careers. And in very different ways, that’s the saving grace for each of them.

I am a folksinger, songwriter, and music journalist, but writing Revival is the most musical thing I’ve ever done. Through the characters, I was able to write about the love of music, what draws us to it, the power it has to help us understand our lives and emotions in such intimate ways. There are passages about why we love sad songs so much, how we create our own meanings and memories for songs, and how music underscores the important moments in our lives. You don’t have to be a musician to understand those things.

Do you have any advice for anyone who may want to write a novel one day?

First, never name any of your drafts the “Final Draft.” I think I had nearly a dozen drafts with the word “Final” on them, including “Final Run-Through” and “Final Tweak.” A book will make up its own mind when it’s done, just like a song does.

There are many stylistic things I learned from traditional songs. They are the foundation of all our storytelling, as well as our music, so they can teach us a lot about how to describe landscape, how to use narrative to reveal character, how to employ techniques like imagery, symbolism, irony, and foreshadowing in ways that feel natural, not manipulative. Most of all, I wanted this story to be real, filled with believable events and knowable people. So there are shimmers of actual people in all the characters, but mingled together enough that none of them are recognizably any single person.

I’ve heard that it’s become a favorite road game among some performers to figure out who each character really is. Meg Hutchinson, one of my favorite young songwriters, said, “What that’s really about is that we all want to be Kit.” I loved hearing that.

Another thing I learned from music, particularly from writing songs, is to listen to the characters. There’s an amazing process in which they come to life and become real people, with their own motivations, authenticity, vernacular and ways of thinking. From then on, they will help you tell their story, if you let them. The question stopped being, “What should Nathan say here?” It became, “What would Nathan say here?” Songs do that when you’re writing them, too, so I was able to recognize it when it happened.

Finally, be prepared for an emotionally wrenching process. I really understand now why some novelists are crazy. You have to believe the story if you want anyone else to believe it. It’s very powerful to be that deeply inside stories and characters that exist only in your imagination and it can also be very painful. You spend so much time within a world that you believe and yet, that you are creating. I went into a tailspin of depression every time I finished a draft, because this real world was suddenly gone, along with all the people with whom I had been so intimately involved, and about whom I cared so much. But writing Revival was also the most artistically joyful thing I’ve ever done, and to see people taking their own joy from it is an even deeper joy.

During the writing of Revival, were you ever able to turn off the story line in your head? Were you always thinking about the characters as though they were living, breathing humans?

There were times I had to get away from it, but I never really could. The characters were so real to me, and there were times when I would miss them, or wish they were with me. I did find myself thinking, “Oh, Kit would love this,” or “I wish Nathan was here to see this.” It can be frightening to be so deeply inside your own imagination, but it’s also exhilarating.

There were times when other work took me away from the book for weeks, or even months. I would become afraid that I’d lost the thread, that the characters would be gone, no longer able to speak to me. But I’ve learned from music that art always returns to you, if you let it and are willing to humbly open yourself to it. And it always did return.

Did anything about the writing process surprise you?

I think that level of involvement surprised me. On a more practical level, I was surprised at how many rewrites it took, how much tweaking and buffing and refining. One draft was entirely focused on making sure that each character was speaking in their own voice, with their own vernacular. Another was looking for timeline inconsistencies, for anything that might happen out of time or place. So each draft got easier and more technical.

And honestly, I think the joy of it took me by surprise. It’s wonderful when imagination and your practical self are able to work side by side. And in my case, it was the first time I felt that the musician and the journalist were equal partners. Writing a novel takes you so deeply inside yourself, involving all your focus, feelings, senses, skills, and dreams. I’m sure I’m not the only writer who finishes a process like that thinking, “I’ll never do that again,” and at the same time, “I can’t wait to dive back in.”

What’s next in the creative life of Scott Alarik?

I’m working on a book that will also be about folk music, but in a very different way. During the Vietnam War, I resisted the draft and spent 19 months in federal prison. I was already a folksinger and did concerts on the compound. That helped me survive in many ways. I learned so much about the universal power of song, how it could connect me to people whose lives were so different than mine. If we are a human family, music is how we express that. It’s why I’ve never doubted the value of folk music, whether the commercial industry sees it or not. We all feel, in some ways, that music has pulled us through dark times, saved our lives. In my case, I believe that’s literally true.

Editor’s Note: Scott Alarik also is the author of a 2003 nonfiction primer on the folk music scene entitled Deep Community: Adventures in the Modern Folk Underground and has written for several music publications. More information on the writer and his book may be found at his website.