In the summer of 1970, when I was just ten years old, my family began what was to be a one-year stay in the San Francisco Bay Area. We were weekending at a small, resort just down the coast, near Santa Cruz; the evening’s entertainment was to be provided by a folksinger and storyteller named Rosalie Sorrels. I guess I was too young to appreciate – or even now, 47 years later, recall the exact experience. But it must have resonated with me considering how active I’ve since become in folk and acoustic music circles. Many years later, I saw Sorrels, who died June 11, in concert and related the experience to her. She told me at the time how she had frequented that resort — whose name escapes me and has long since closed – – for years and how much she enjoyed spending time there.

In the summer of 1970, when I was just ten years old, my family began what was to be a one-year stay in the San Francisco Bay Area. We were weekending at a small, resort just down the coast, near Santa Cruz; the evening’s entertainment was to be provided by a folksinger and storyteller named Rosalie Sorrels. I guess I was too young to appreciate – or even now, 47 years later, recall the exact experience. But it must have resonated with me considering how active I’ve since become in folk and acoustic music circles. Many years later, I saw Sorrels, who died June 11, in concert and related the experience to her. She told me at the time how she had frequented that resort — whose name escapes me and has long since closed – – for years and how much she enjoyed spending time there.

An Idaho songbird who wrote heartfelt, expressive, often deeply personal songs of love and loss, loneliness, poverty and social injustice, and sung them in her fluid, mellifluous yet sometimes heartbreaking voice, Sorrels passed away at the Reno, Nevada home of her daughter Holly Marizu, where she had been living for the past several years. Although the cause of death was undetermined, Sorrels, 83, had been suffering from dementia and colon cancer. Nearly 20 years earlier, she had beaten breast cancer after having suffered a cerebral aneurysm ten years earlier in 1988.

Sorrels also was a folklorist and a collector of folk songs of all kinds – ranging from English ballads to Mormon songs and the works of contemporary songwriters — who had a near-encyclopedic knowledge of musicology.

Five generations of her family lived and worked in Idaho. Her paternal grandfather, Rev. Robert Stringfellow, was an Episcopalian preacher who came to Idaho during the state’s early years, while her grandmother, Rosalie Cope Stringfellow, for whom she was named, was a photographer and journalist. Interestingly, her maternal grandfather, James Madison Kelly, was “an Irishman and an Atheist,” who she recalled “having cursed at his horses in Shakespearean language.”

Many of her family members were storytellers, and Sorrels grew up surrounded by books and songs and immersed in ideas and poetry She was born in 1933 and lived in Idaho for many years in a cozy handmade cabin that her father, Walter Stringfellow, a piano-playing and musical-loving engineer, had built on Grimes Creek, located in the mountains near Boise, the state capital. Her mother, Nancy Stringfellow, who ran a bookshop in downtown Boise and through whom she acquired her love of literature, had named the cabin “Guernica,” meaning “little place that holds your heart.” Although she later returned there, Sorrels left Idaho at age 19 — determined to see the world beyond its boundaries.

In the early 1950s, she married Jim Sorrels, whom she met while both were performing at the Boise Little Theatre. A few years later, they moved to Utah. She launched a career as a folklorist at the University of Utah during the 1950s and also taught folk guitar classes there and promoted concerts in the area – including Joan Baez’ first Salt Lake City appearance.

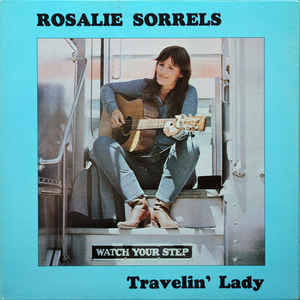

After 14 years of an often stormy and abusive marriage, she left her husband and Salt Lake City in 1966 and with her five children headed back home to Idaho. Taking to the road, Sorrels followed her true passion – music – with her children in tow – embarking on a lifetime of traveling that resulted in her being known as the Travelin’ Lady, also the name of one of her early songs and albums, which tells of her divorce and heading out on the road. For a brief period of time, she and her children lived in Saratoga Springs, New York with Lena spencer, founder of the famed Caffe Lena there.

After 14 years of an often stormy and abusive marriage, she left her husband and Salt Lake City in 1966 and with her five children headed back home to Idaho. Taking to the road, Sorrels followed her true passion – music – with her children in tow – embarking on a lifetime of traveling that resulted in her being known as the Travelin’ Lady, also the name of one of her early songs and albums, which tells of her divorce and heading out on the road. For a brief period of time, she and her children lived in Saratoga Springs, New York with Lena spencer, founder of the famed Caffe Lena there.

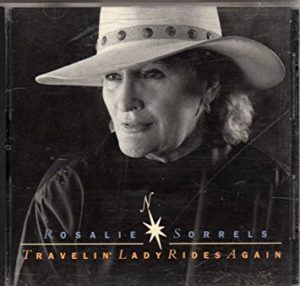

During a career that spanned more than six decades, Sorrels recorded more than 25 albums and appeared on many others. She performed at numerous clubs and venues and at many major music festivals. She graced stages at the Newport Folk Festival in 1966 (where she first drew notice while performing with Mitch Greenhill) and Woodstock in 1969 (where she jammed with Jerry Garcia), and received a standing ovation following her performance at the 1972 Isle of Wight Festival. Sorrels continued performing actively through the 1990s, touring both as a solo artist and with longtime close friend Bruce “Utah” Phillips. Health issues prompted the “travelin’ lady” to cut back on her touring and eventually retire to her home in Idaho during the next decade. However, she returned to the studio in 2007 to record an album, the Grammy-nominated Strangers in Another Country: The Songs of Bruce “Utah” Phillips, to benefit her friend who had congestive heart failure and died the next year.

Considered among the top artists of the Beat Generation, Sorrels earned the admiration and friendship of such famed writers as Hunter S. Thompson and Studs Terkel, both of whom wrote liner notes for her. Thompson, the gonzo journalist and author of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, referred to her songs as “so close to the bone, I get nervous listening to them.” A Rosalie Sorrels Archive is maintained as part of the Beat Generation Archives at the University of California at Santa Cruz.

Through the years, Sorrels also earned praise from the Boston Globe, which hailed her as “one of America’s genuine folk treasures” and from fellow folksingers and storytellers like the late Gamble Rogers, who called her “the hillbilly Edith Piaf.” Sorrels, who was herself influenced by Malvina Reynolds, also helped to inspire a new generation of folk artists during the 1980s – including such notables as Mary Chapin Carpenter, Guy Clark, Nanci Griffith, Christine Lavin, and Tom Russell.

Although most of the songs Sorrels recorded and performed (accompanying herself on acoustic guitar), she also helped to preserve the oral folk tradition through her fine interpretations of traditional songs and those written by others. Sorrels also wrote or co-authored several books — including Way Out in Idaho, a collection of songs, stories, poems and recipes published by the Idaho Commission for the Arts in connection with the state’s centennial celebration in 1991.

Sorrels received two Grammy Award nominations, the Idaho Governor’s Award for Excellence in the Arts in 1986, the World Folk Music Association’s Kate Wolf Award in 1990, a Circle of Excellence Award from the National Storytelling Network in 1999 for “exceptional commitment and exemplary contributions to the art of storytelling,” and an honorary Doctorate of Fine Arts from the University of Idaho in 2000. She also was a featured artist in the Smithsonian Institution’s Founding Members of Folk exhibit and accompanying recordings.

Besides her daughter Holly, Sorrels leaves behind another daughter, Shelley Ross, a son, Kevin, her brother Jim, five grandchildren and two great grandchildren. Her eldest son, David, committed suicide in 1976, and she paid tribute to him in her plaintive song, “Hitchhiker in the Rain.” Another daughter, Leslie, died last year.

A multi-CD set of songs entitled Tribute to the Travelin’ Lady is expected to be released soon and may expose Sorrels’ songs to a new generation.

Here’s a link to a video promoting an Indiegogo campaign to raise funds for the tribute album.

https://www.indiegogo.com/projects/rosalie-sorrels-tribute#/

Like/Follow Us!