By Sharon Goldman

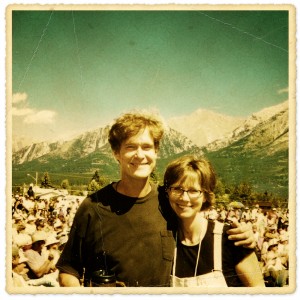

Editor’s Note: As president of the Folk Music Society of Huntington, a Long Island, New York-based presenting organization, I had the pleasure of introducing Tracy Grammer to kick-off our 2011-2012 concert season last October. Ten years earlier, in July 2002, I’d seen her and Dave Carter perform at Huntington’s Heckscher Park in a concert co-presented by the society. Sadly, it was to be the last time I’d see Dave Carter. A few days later, and three weeks shy of his 50th birthday, he died following a massive heart attack. Just days after Carter passed away, Grammer – who first met him at a songwriters’ showcase shortly after she moved to Portland, Oregon in 1996 and began touring with him the following year – foretold her musical future in a letter she posted on their website: “We need to keep this music alive; it was always my mission that the world would hear and know the poetry and vision and wonderful mystical magic of David Carter. This path is broad and long; I hope you will stay the course with me.”In the years since, Tracy Grammer has continued to tour internationally and has been a staple at a number of folk festivals. With her warm and emotive voice, she is keeping Dave Carter’s music alive while sprinkling a few traditional tunes and some of her own songs into her performances.Her solo debut, Flower of Avalon, was the most played album on folk radio in 2005. The following year, she released Seven Is The Number, the last full-length Dave & Tracy CD. Earlier this year, Red House Records released Little Blue Egg, a collection of archived home and studio recordings that the duo made between 1997 and 2002. The album topped the Folk DJ chart in February and also sported nine of the month’s top songs.“Way over Yonder in the Minor Key,” was reportedly the most-played song on folk radio during the month.

Sharon Goldman, a New Jersey-based singer-songwriter, recently spoke with Tracy Grammer for Songwriting Scene, a blog for songwriters about songwriting that she launched in 2009. Her article is re-posted here with permission.

Sometimes you hear a singer-songwriter and you immediately understand the difference between the truly talented genius and the workaday creative types. The “Wow” factor was definitely at work when I first heard a tune by folk singer-songwriter Dave Carter called “Tanglewood Tree,” which includes the following lyrics:

Love is an old root that creeps through the meadows of sleep

When the long shadows cast

Thin as a vagrant young vine, it encircles and twines

And it holds the heart fast

Catches dreamers in the wildwood with the stars in their eyes

And the moon in their tousled hair

But love is a light in the sky, and an unspoken lie

And a half-whispered prayer

Those lyrics, along with a beautiful arrangement and background vocals with Carter’s duo partner, Tracy Grammer, truly blew me away and led me to explore more of Carter’s work, with its poetic imagery and beautiful storytelling — and to discover, to my dismay, what I had not realized: that Carter had passed away suddenly and unexpectedly in 2002.

I had, apparently, missed out on an amazingly talented artist who was in the midst of growing fame, who was heralded as the “new voice of modern folk music” in the months before his death. He and Grammer toured with Joan Baez in 2002; released several critically-acclaimed recordings including Drum Hat Buddha, Tanglewood Tree and When I Go; and performed at a wide variety of top festivals and venues around the world in the six years that the two performed as a duo.

Here’s a video of Dave Carter and Tracy Grammer singing their classic “Tanglewood Tree” in 2000:

Now, on the 10th anniversary of Carter’s death, Grammer — who has served as the “keeper of the flame” regarding Carter’s songs — has released a new collection of archived and rediscovered home and studio recordings of Carter-Grammer tunes, Little Blue Egg. I was honored to have the chance to chat with Tracy Grammer about her memories regarding Dave Carter’s creative process as well as his songwriting habits, advice and inspiration:

Q: Do you remember the first song you heard Dave Carter sing, and what you thought at the time?

Grammer: I remember it very clearly; it was at a songwriter’s night in Portland, Oregon, where everyone gets up and plays two songs. I was there with another guy named Dave, and we played our songs, and then everyone starting shushing each other because Dave Carter was about to play. It was clear that he was a big deal. And he started singing this song “Gunmetal Eyes,” which is about a young Native American man who takes a stand against some guys who are razing the land. He went on to play a couple of other songs that were really different — I think one was “Snake Handlin’ Man,” which is more of a bat-out-of-hell evangelical thing with a lot of fast finger-style guitar no one else could do. It had crazy speaking-in-tongues lyrics, and his mother really did used to speak in tongues. I remember thinking that what he was singing about was different, not your usual singer-songwriter, navel-gazing fare. He used a lot of the language of poetry and had moving, intelligent stories, with simple chords, that resonated with me. And it had a little bit of a twang. It was soul music to me, but I wasn’t going to say anything to him that night. However, he saw I had a violin and the next thing I knew, he asked me to be in his band.

Q: What do you remember most about Dave Carter’s writing and creative process?

Grammer: Part of his academic background was in transpersonal psychology, and he was actually trained in mining the dream realm, so he really knew how to go down that route almost like it was a shamanic journey. Songs would come to him in dreams — he knew how to recognize when something was valuable in a dream, and he could even hang around longer in a dream if he needed to dig a little deeper down the rabbit hole and root around. He might have a song idea walking around, but there was always a bit of him processing on different levels. Of course, there’s more to the process than the dream stuff; that would be the genesis, but then he’d wake up and he’d do what he told his songwriting students to do — he’d get involved in some kind of rhythmic activity, like walking, running or biking, and start spinning out rhymes and nonsense lyrics until the thing started to take shape. Then he would come back, sit down and get an instrument out. He was such a strong trained musician, he could find things easily on a guitar or keyboard and write stuff out. He’d send me versions and drafts — I got a new song nearly every other day. Things didn’t change much after that — he finished songs quickly for the most part. There are some he might do more actual intellectual work on — for instance, after he died we went through his computer and he had a lot of bookmarks on antiquated dictionaries with funky old language. But he also would just hear a word in his head and hunt it down in all these dictionaries — he trusted sounds to have their own innate meaning.

Q: What do you miss most about working with Dave?

Grammer: I miss our process — he was so prolific, it was really like call-and-response. He would have a song, and I would respond to it musically. It was interesting, fun and refreshing for me because he made me feel like I was part of the process. I can’t say I co-wrote songs with him — I was very aware and my thing when I first met Dave was to say, “This is about the songs; don’t put my name on it.” And then he just put me on there. But I always thought it was about the song, and my role was how could I serve the song. The process was magical and intuitive; we didn’t argue, we didn’t discuss them a lot, we just played. It was really natural, which is what made it such a joy. Of course, something had to be easy — the travel wasn’t easy, and we were broke all the time, so it’s good making music was easy! Recording, on the other hand, was awful for us. Dave was a horrible perfectionist and really self-deprecating in the studio. It was funny but could almost be poisonous. It was better when we got a little budget and we could work in a studio where he had to tone it down in front of the engineer. The things is, we had no idea we’d go national within a year of working together, and we wanted to give it our best but had no idea what we were doing. We felt a lot of pressure to be really good. And he just wanted it to sound true.

Q. What was it like for you to discover and hear the tapes that eventually turned into your new release, Little Blue Egg?

Grammer: I knew I had the tapes, but I was just putting off listening to them. The format was an old technology. I was nervous, as I’ve said many times before, that the tapes would be damaged. So, the first thing I felt was pure joy — because the first song I heard was “Cross of Jesus,” which I had thought about a lot since he died. But I couldn’t remember all the verses, and I didn’t know where any copies of that song might be. It was something we had left on the cutting room floor, so I was delighted because we had worked so hard and it sounded really good. It was great to hear Dave singing, he sounds so happy. It reminded me of how hard we worked to get it so right in our little house in Portland, Oregon. We were so earnestly doing these projects. It also brought into focus how fast things were going — we did this stuff and then we were back on the road. At the height of it we might have done 180 shows in one year.

It was great to hear Dave singing, he sounds so happy. It reminded me of how hard we worked to get it so right in our little house in Portland, Oregon. We were so earnestly doing these projects. It also brought into focus how fast things were going — we did this stuff and then we were back on the road. At the height of it we might have done 180 shows in one year.

Q: Is there anything you wish could happen with Dave Carter’s songs that hasn’t happened thus far?

Grammer: Well, I’ve basically done a lot of work singing the songs, and I’ve made sure some songbooks were available and old recordings got out there. But I feel like I’ve fallen down on the job of finding Dave a proper publisher or getting his songs placed in movies. I have this vision all the time of the song “When I Go,” that the banjo could start the movie, I totally hear it. I feel like I haven’t been as impactful, I’ve done what I could on zero budget, and it’s self-sustaining — what the career gives me is what I have to work with. But it will be great when a publisher gets hip to this catalog and maybe offers it to bigger-name artists and Dave gets more exposure as a songwriter. There are certainly people out there who are also mining a similar, mythic-poetic-spiritually-tinged realm, singers for whom these songs would resonate. I mean, all of the rock stars of my growing up would be fine candidates! I’d love to see Bruce Springsteen doing “Farewell to Saint Delores”. And Mary Chapin Carpenter recorded “Ordinary Town” for a project of covers she eventually scrapped, but I would have loved to hear it. Oh, and Joan Baez recorded “The Mountain” but never released it.

Q: What are the Dave Carter lyrics that resonate for you the very most?

Grammer: When Dave died and I went to the hospital to see him, the first words that came to me were “Fly like the falcon,” from “When I Go.” It was uncanny because at the end of that week we were supposed to perform at the Falcon Ridge Folk Festival. But it was a key lyric in a moment I wasn’t expecting to find a mantra. Also, I think the most potent lyric for me personally and for our relationship and what Dave did for me as an artist and person comes from “Farewell to Saint Delores” — “The ageless face that that witnessed me for certain when my own could not be found.” We had had a conversation about his stories, and I said “You have so many stories, but I don’t have any stories.” And he said, “Yes, you do, baby, you have a ton of most excellent stories.” I thought I was a person without stories, and I didn’t see myself as a musician or an artist or anything but a glorified cheerleader. But he reminded me all the time — he gave myself to me. And the reason I’m drawn to his music is that it pieces me together and fills in the blanks of the spiritual training I never got, or the gaps in who I am. I feel completed by this music — I am this music.

Q: What kind of advice do you think he would give inspiring songwriters today?

Grammer: He would say it’s important that the story be true, emotionally true. He would probably advise that thing that writers always say, “Write what you know.” But it’s not just that you write about the one little town you live in, but the feelings come from an authentic place. He also did love the idea of those rhythmic exercises and getting the body involved in songwriting. He didn’t think you should censor yourself too early in the process. He said you had to give it room to play. Also, Dave was also always pretty adamant that people shouldn’t be too clever musically. You should just serve the story — don’t just throw in random acrobatics or funky little chords just because you think they’re cool. On the other hand, he was not afraid to be intelligent for his listeners. He never dumbed things down. People would get it, and one of the lasting gifts of his songs is that for some of us they’re a challenge — you might not be sure what it means at first, but it makes some kind of sense, even if it’s just on a musical level. And then the more you listen, the more it gives to you; it keeps revealing.

Like/Follow Us!